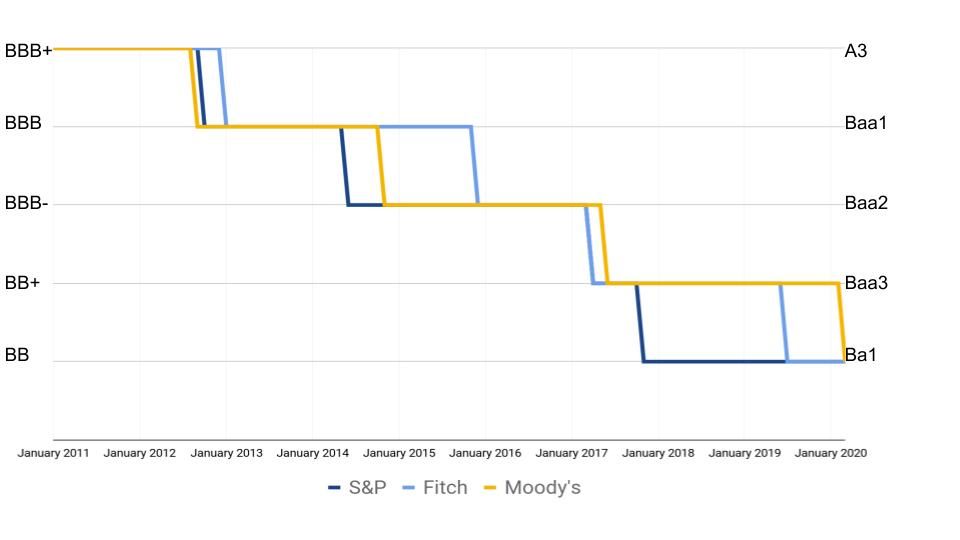

In 2017, 2 of the 3 major ratings agencies (Fitch and Standard & Poors) downgraded South Africa’s credit rating to sub-investment grade (junk) status. Last week, Moody’s did the same.

Why did this happen and what are the implications?

Background

South Africa’s finances have been strained for a while now as a result of many well reported issues - weak growth, high unemployment, high debt, state-owned enterprises like Eskom requiring numerous bail-outs (and not providing a stable supply of electricity) as well as general maladministration. Investors had lost confidence in South Africa and its ability to implement the tough and unpopular reforms required in order to turn things around.

It seemed as though things were beginning to get better in this regard after the budget speech last month (see Tightening the belt) where the Finance Minister stated that the public sector wage bill was going to be significantly cut, however the impact of the major economic slowdown here and worldwide as a result of the coronavirus pandemic (see Ay Corona!) forced Moody’s hand into downgrading South Africa’s credit rating.

Borrowing power

One of the ways the government raises money is by borrowing from entities like banks and fund managers. Generally, the better the country’s credit rating, the easier and cheaper it is to raise money. Moody's downgraded South Africa's credit rating as they think there is now a higher chance the country may not be able to repay its debts when they fall due.

Some financial entities can only lend to/invest in countries with a certain level of credit rating or higher (investment grade). Now that South Africa falls out of this category, many of these entities that had previously invested in South Africa are forced to sell their investment. Given supply and demand dynamics, if lots of people are selling - the price falls.

South African bonds will now also be excluded from the World Government Bond Index which means that investors or funds that want to replicate the investments of this index will no longer have to invest in South African bonds and these investors will also sell out, putting further pressure on prices. These sales will also cause the rand to weaken, something that the markets have already priced in - the Rand is now at an all time low against the US dollar.

As the prices of bonds fall, their yields rise. This means that South Africa now needs to offer a higher return to new investors in order to get them to invest (pay a higher interest rate). This costs the country more, increasing its debt level even quicker than before (high debt was one of the issues that got South Africa in trouble in the first place and now is getting worse).

South Africa’s options in terms of borrowing money will be severely reduced. It’s almost like all of the big banks telling you you can’t borrow money from them any more and that you have to go to a loan shark!

Where to from here?

The country would normally have a tough enough job getting out of this predicament but the impact of the current lockdown and the reduction in economic activity that comes with it have made things much worse. That said, it may actually work to South Africa’s advantage in the long run.

Now there is no doubt that the government has to make wholesale changes given the double whammy of the downgrade and the impact of coronavirus - half measures will no longer work: there can no longer be any wasteful expenditure on state-owned entities, the public sector wage bill cuts have to happen, and other policies like increased broadband spectrum allocation, labour and tourism flexibility need to be put in place quickly in order to aid the country’s finances and stimulate the economy.

Countries like Egypt and Brazil have been through what South Africa is going through now and have not fully recovered yet, so it may take years to turn around. Borrowing money from the World Bank or International Monetary Fund could also be an option for South Africa as they lend to countries that are in trouble in order to promote stability. However that money would typically come with firm conditions of what the country would need to do to turn things around and our government may not like terms being forced upon it, although it may not have any other choice.

The resolve of the country and its people will be severely tested in the short and medium term but South Africans have a reputation for being most resolute when things are at their worst - it is just unfortunate that we need to get there in the first place. As our president recently wrote: "This too shall pass. We shall overcome. We are South Africans."

![The Guide To Provisional Tax In South Africa [+ downloadable provisional tax calculator]](/blog/content/images/size/w600/2025/09/calculating-your-provisional-tax.png)